Bishops versus Knights (a general assessment)

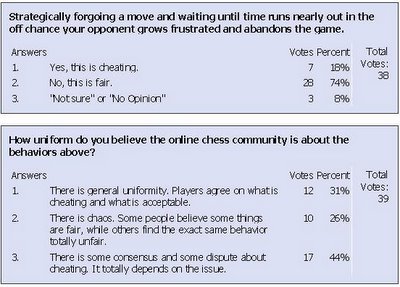

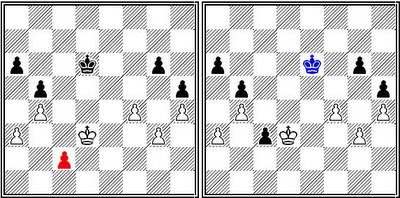

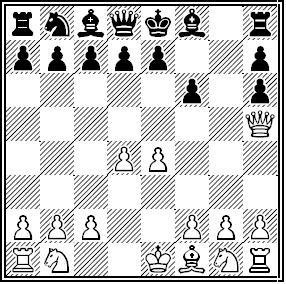

While assessed as equals throughout the chess match, there are many situations where a bishop can dominate a knight. The key is placement of either piece. The knight’s principal disadvantage is that at the absolute most it has only 8 squares it can move to (even in the middle of the board). In the worst case scenario (a corner like h8) it has only two! A bishop on the other hand, in the center of the board has 13 squares it can move to; and even in the worst of situations (again h8 for example) it has 7 possible moves. Based on this mobility gap, a bishop can easily render a poorly placed knight worthless. For example, take Diagram 1 (left).

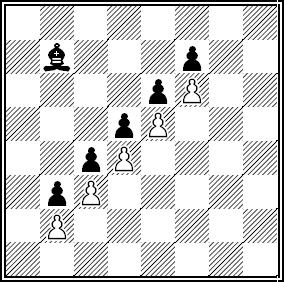

While assessed as equals throughout the chess match, there are many situations where a bishop can dominate a knight. The key is placement of either piece. The knight’s principal disadvantage is that at the absolute most it has only 8 squares it can move to (even in the middle of the board). In the worst case scenario (a corner like h8) it has only two! A bishop on the other hand, in the center of the board has 13 squares it can move to; and even in the worst of situations (again h8 for example) it has 7 possible moves. Based on this mobility gap, a bishop can easily render a poorly placed knight worthless. For example, take Diagram 1 (left).The d8 knight is totally controlled by the bishop. If the knight dares to move to any of the “x-squares” it will be immediately captured.

Thus, as a simple mater, the basic chess rule once again applies – centralize your pieces and try to force your opponent’s pieces away from the center. As shown above, this can prove key in knight versus bishop scenarios.

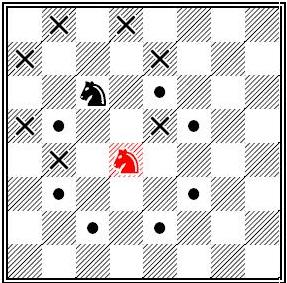

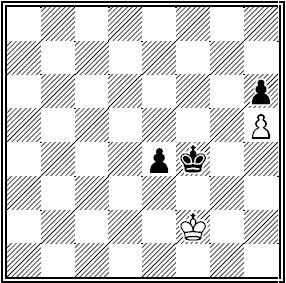

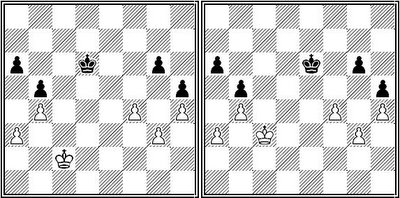

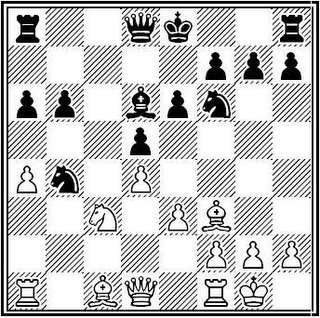

As another introductory matter, an unusual characteristic of the knight must be noted – it cannot move and guard any of the squares it previously did. For example, imagine a knight on c6 (Diagram 2; left). It guards 8 squares (marked as “x-squares” below). Now imagine that knight moving to d4. Note how none of the new squares guarded by the knight (marked as “dot-squares” below) match the previous squares guarded.

As another introductory matter, an unusual characteristic of the knight must be noted – it cannot move and guard any of the squares it previously did. For example, imagine a knight on c6 (Diagram 2; left). It guards 8 squares (marked as “x-squares” below). Now imagine that knight moving to d4. Note how none of the new squares guarded by the knight (marked as “dot-squares” below) match the previous squares guarded.The knight is the only piece that possesses this unique characteristic. The puzzled reader is probably thinking to themselves, why does this matter? Basically, what this phenomenon amounts to is that the knight cannot “lose a turn” or “lose a tempo.” Thus, zugswang positions haunt knights. In knight versus bishop endgames, this theme becomes especially important – since a bishop can very easily lose a tempo.

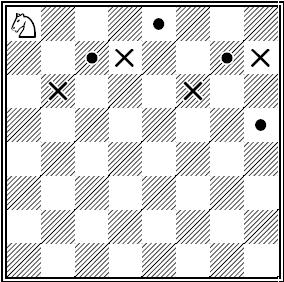

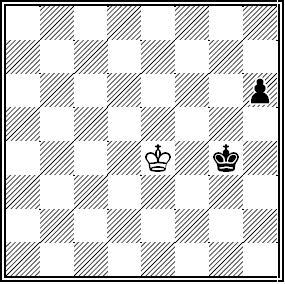

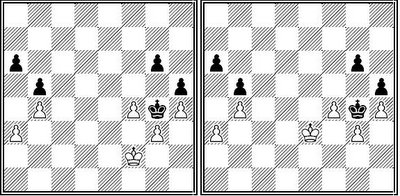

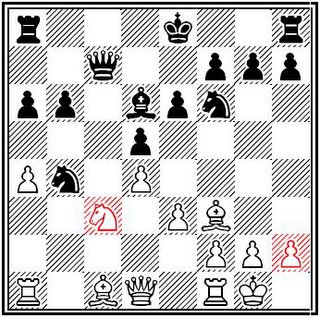

As a final obvious, but important note. One must note the speed gap between knights and bishops. Imagine a knight on the a-file. For the knight it does not matter where, but let’s assume a8. (Diagram 3; left).

As a final obvious, but important note. One must note the speed gap between knights and bishops. Imagine a knight on the a-file. For the knight it does not matter where, but let’s assume a8. (Diagram 3; left).No matter what route it takes, it will take exactly 4 moves to get to the h-file. (I chose two routes in the diagram above, one noted by “x-squares” the other by “dot squares.”). Now compare this with a bishop on a8. It takes just one move to get to the h-file – 1. Bh1!. Even on a less than ideal square, say a4, a bishop can get to the h-file in just two moves. 1. Bd1. 2. Bh6. The basic point is clear – a bishop is much better than a knight when there is action on both sides of the board. This will become key in knight versus bishop situations. If there is strong play on both sides the king and queen sides, a bishop is much better than a knight.

So far we have taken a pretty critical view of the knight – surely it has some advantages over the bishop! Indeed it does. Again, it is important to note the obvious. First, a knight can travel to every single square on the board. It might take it several moves to do so, but a knight can get to any white or black square. This is, of course, not so true of a bishop who is confined to just one set color of squares.

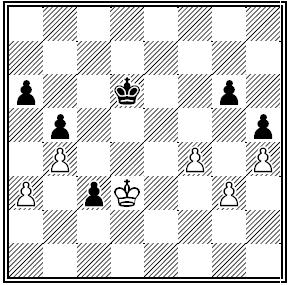

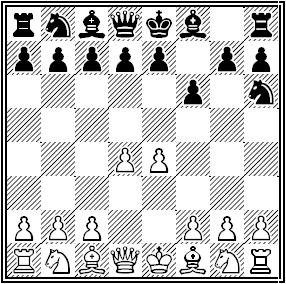

Second, again painfully obvious, the knight has the ability to jump over other pieces. Especially when pawn formations become stagnant bishops can become “bad” and virtually an oversized pawn. This will not be true with knights who can often leap over even the most fortified of pawn entanglements. As an exaggerated example, note Diagram 4 (below/left):

The poor bishop can make absolutely no headway in this position. It is locked out from virtually half the board. A knight in the same position could get through (albeit with time). The knight could get to a4 and attack the base of the white pawn chain or it could get to f8 and simply go around it.

The poor bishop can make absolutely no headway in this position. It is locked out from virtually half the board. A knight in the same position could get through (albeit with time). The knight could get to a4 and attack the base of the white pawn chain or it could get to f8 and simply go around it.

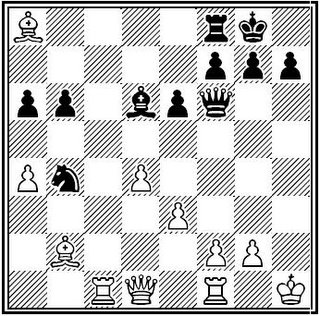

NN vs. Hypermodernprodige (Black to Move)

NN vs. Hypermodernprodige (Black to Move)

One of those pieces must now fall. The logical choice is, of course, saving the knight, with 2. Bb2 probably being the best move. But after 2... Bxb2, black has a not only a solid pawn advantage, but white's king-side is seriously weakened.

One of those pieces must now fall. The logical choice is, of course, saving the knight, with 2. Bb2 probably being the best move. But after 2... Bxb2, black has a not only a solid pawn advantage, but white's king-side is seriously weakened.